Processes of the Perth Kirk Session

Share this step

The elders met in general about weekly to address disciplinary and administrative problems.

In the 1570s there were quite frequent additional, ad hoc meetings, so that in October of 1578, for instance, there were eight meetings. In the calendar year 1579, a representative year for the period of this transcription, there were fifty-nine meetings. By 1597 there would be two discipline days weekly (Monday and Thursday), with a third meeting added on Tuesdays in 1598 for hospital business. From 1601 elders were required to attend Friday morning prayers before visiting families in their quarters, although this order had to be repeated in 1605, when the Tuesday meeting was devoted to poor relief, and hospital business moved to Thursday. The session would add a regular Friday meeting in 1621, and in fact disciplinary matters were handled on most of the meeting dates. The elders were also expected to attend presbytery meetings on Wednesdays. In short, eldership was an onerous burden on men with businesses to run. Fines levied by nearly every session in Scotland for absence from meetings and lapses in punctuality suggest that some elders bore it grudgingly. Only rarely, however, did anyone try to decline the office, which clearly carried considerable power and status along with obligation.

The most frequent issue handled by the session and recorded in the minutes was the approval of marriage banns. The procedure from June of 1578 was for a couple to seek the sessions approval at least forty days before their proposed marriage to have their banns publicly declared on three successive Sundays. The elders clearly presumed that couples would be sorely tempted to jump the gun in the interim, so to ensure their circumspect behaviour and the timely solemnisation of the marriage, they required each partner to secure a ‘caution’ (or ‘kation’) – a surety or responsible party who would have to pay a hefty fee in case the couple engaged in antenuptial fornication or failed to follow through on their contract by the stated date. Cautioners were generally men of substance, though there are four examples in this volume of women serving in this capacity. They were often kin or masters – people with an acknowledged obligation to watch out for their charges – but sometimes there is no apparent relationship between the young person and the cautioner. Given the risk of heavy fine for inadequate supervision, one wonders why people would be willing to perform the service, especially for known fornicators; status value seems the likeliest explanation. Readers of session minutes may initially regard the great number of marriage cautions listed as rather a waste of space, but these names provide a window on social networks in the burgh. And there are other, larger implications of caution listings. Cautions were (and remain) a staple of Scots law; here we have an example of the elders adopting an already familiar mechanism to enforce the new protestant discipline. The incidental benefit to the kirk’s poor box when a couple breached their contract or a woman was found to be pregnant too soon after a wedding was also considerable: the session did in fact enforce collections of the ‘punds’ or penalties from cautioners, and the poor benefited.

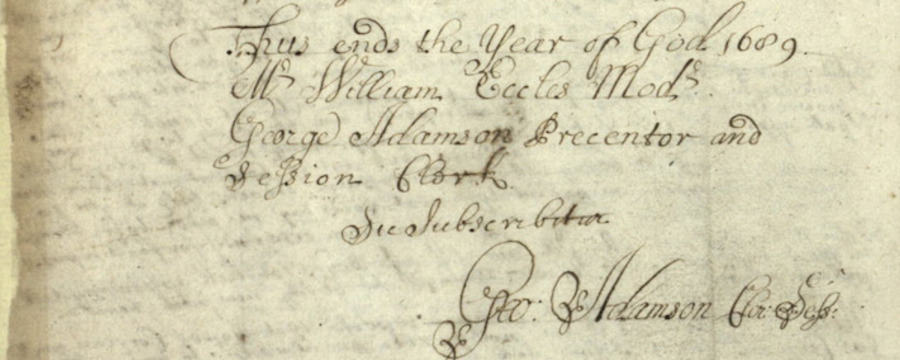

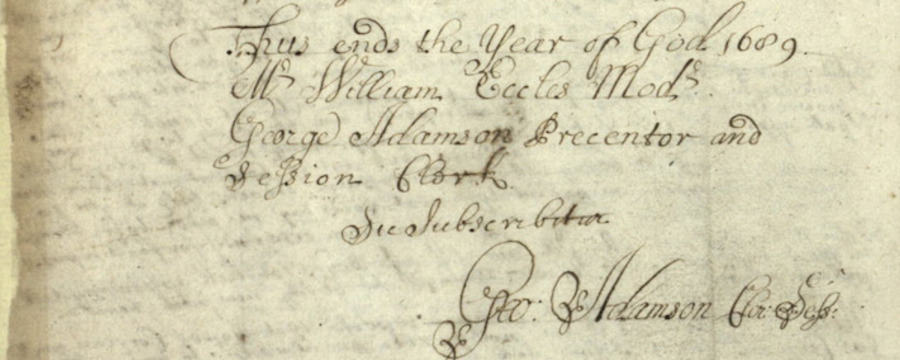

The session adopted and adapted contemporary bureaucratic as well as legal conventions to facilitate efficient administration of discipline, both preventive (as in the case of marriage banns) and punitive. One of these was simply the keeping of minutes — written records of acts and obligations by which people could be held to their promises. In the Perth minute book, the clerks’ development of quite specific forms of marginalia for quick reference is noteworthy. To help himself keep track of compliance with the deadlines for solemnisation of marriages, next to an entry for banns in the register the clerk jotted a number each time the banns were proclaimed, and when ‘3’ was reached made sure that there was a date recorded for the wedding, and for whatever fee might be due. A glance at the margins would draw the attention quickly to couples who might be reneging on their contracts, so that the cautioner could be summoned before the session. The system worked to track punishments as well: when six sabbaths of public repentance (see below) were required before a penitent could be absolved and received back into the congregation, we find the numbers of penitential performances jotted in the margins next to the entry in which the offender was sentenced, together with a code to explain the sentence (‘c2’ for ‘culpa 2’, a second offence for a sin that required multiple Sundays of penitence for each sin) and a code for the outcome (‘R’ for ‘received’, or perhaps a date for absolution, and an amount for a penalty paid). The numbers appear in different shades of ink: one can imagine the clerk taking the session book with him to church and keeping his accounts of penitence and banns as they happened. If a sinner failed to complete the required penalty, a glance at the margins would alert the clerk to have the officer summon the offender again. Perth’s session clerks deserve a place in the history of early modern bureaucracy, and those who would understand the pervasiveness and efficiency of Reformed discipline would do well to attend to bureaucratic convention, not just theology and preaching.

Another mechanism for administering the new discipline was systematic visitation of the quarters of the town by assigned elders to ensure the doctrinal orthodoxy and good behaviour of families. This was done in particular before communions, when each elder was assigned to visit and examine his designated families, instruct and admonish them, and take down a list of those qualified to be admitted to communion. The session distributed communion tickets or tokens to members of approved families, generally just before the Saturday ‘preparation’ sermon which preceded the Sunday communion; designated elders or deacons then collected these material signs of orthodoxy and upright behaviour at the kirk door on communion Sunday. The elders also visited their allotted neighbourhoods regularly, assisted by bailies, to ‘inquire of the names of the poor within their quarters’ so that the deserving local poor might be separated from outsiders and be listed to receive alms.

‘Searchers’ constituted another procedural mechanism that the elders found useful to catch out sinners by making surprise visits to their homes or to local taverns. Other sinners were reported by their neighbours, and even if no one had witnessed a suspicious action, the ‘bruit’ or rumour of misbehaviour was enough to initiate a case. Finally, improbable as it may seem to modern observers, some people apparently came voluntarily to confess their sins to the elders.

Most people to be charged with offences were summoned by the kirk officer at the session’s behest to ‘compear’ (appear) before the elders. If they failed to do so, they would receive two more warnings or summons and then could be fined for contumacy. Repeated contumacy could result in warding (gaoling), with the town magistrates responsible for seizing the recalcitrant. The ultimate ecclesiastical sanction was excommunication, at least in theory: this penalty was in fact rarely used. By 1581, the elders were sufficiently annoyed by failure to appear that they adopted an ‘Act of disobedient persons’ mandating immediate warding for anyone ‘being warned and not compearing’, though payment of a heavy fine would release the offender upon promise to come to the next meeting.

A person charged and guilty was best advised to confess the offence; lying about it at first and admitting it later often produced a greater penalty. One who insisted on innocence was constrained to prove it, though evidentiary rules differed from those of modern courts. In the very first case in this volume, the elders told a man who denied fathering an illegitimate child that he must swear an oath to that effect. Such oaths were generally held as proof – testimony to the seriousness with which sixteenth-century people took swearing. Jhon Swenton, the man charged in this case, was given a week to consider whether he would swear, and as the elders probably expected, at his next appearance he declined to give his oath. This they construed as tantamount to an admission of guilt, and indeed he confessed his sin at the next appearance. A woman’s oath bore as much weight as a man’s in these records: it was the oath of Swenton’s partner that convinced the elders to investigate his paternity in the first place. A few months later, her charge that he had ‘made a faithful promise of mariage to her before the begetting of the last bairn’ was also referred ‘simply to her oath’, and her word was accepted. There were hierarchies of oaths, left over from medieval practice. Taking one’s ‘great oath’ or swearing ‘the holy evangels touched’ (with hand on the Bible, as Swenton did in response to his partner’s second oath) was most convincing. An oath taken in circumstances where lying was thought impossible was likewise beyond doubt, as in the case of a woman in labour identifying her child’s father, or when the oath was taken in the physical presence (‘in the face’) of the contesting party – prima facie evidence of truth-telling.

When the elders were unconvinced by pleas or testimony they had heard, they often summoned witnesses to depone the truth of a matter. Again it is noteworthy that the testimony of women was taken as lawful and reliable, a stance which the elders quite self-consciously debated in a 1582 case of notorious adultery: they ‘conclude[d] with one voice that famous women ought to bear witness in any matter that comes before them and their testimony received so far as the law permits’. When all the evidence was in place, the session decided on an action. In most cases, decisions seems to have been consensual, so that the ‘haill elders’ could act as one; sometimes, however, a division was recorded, either with the statement that ‘the most part’ of the elders ruled, or with a list of dissenting voters: on 12 July 1585, for example, Dioneis (Dionysius) Conqueror and William Hall voted against their colleagues not to excommunicate a pair of sexual offenders – perhaps because one of them was a brother of Hall’s guild, the baxters. And on 11 September 1581, only ‘the greatest part of the assembly’ ordered an elder’s wife, Jean Thornton, to be summoned to answer for adultery with another elder, Henry Adamson. One can easily guess who was among the dissenting voters.

In particularly troubling and uncertain matters, the elders provided detective services, in 1584 investigating a rape charge, for instance. The following year, when a woman suspected of fornication claimed to have spent the night in Kintolloch with a female friend, the minister asked one of the burgesses travelling through the village on his way to Loch Levin to ask the friend whether the Perth woman was really there; the burgess reporting that there was no such woman in Kintolloch, the session had its doubts resolved. The session’s arm was long. Even in more mundane cases, communication between parishes allowed the elders to investigate suspicious circumstances: couples who claimed that their marriage banns had been proclaimed in another parish, for instance, had to produce a testimonial to that effect from the clerk or reader of that kirk. This document was then scrutinised by the session, always aware of the black market that had grown up in forged testimonials.

Excerpt from Margo Todd (ed.), The Perth Kirk Session Books 1577–1590. Series six, vol. 2 (Scottish History Society, 2012), pp. 31-36.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free