Perth kirk and its records: the manuscript

Share this step

The story of the Scottish Reformation is one oft-told from the top, as the outcome of actions by monarchs and regents, bishops and preachers, parliament and the militant Lords of the Congregation.

That traditional account is by no means false or unimportant, but it is a truncated version. The Reformers sought to change the hearts and minds of the Scottish people, to free them from what they regarded as popish superstitions and teach-them a new understanding of how they were saved — by grace alone, through faith, as they believed the Scriptures taught. They were certain that what would emerge from a population thus enlightened would be a godly community, as free of immoral behaviour as of the old images, ceremonies, and festivities now condemned as idolatrous. The godly nation would be a praying and fasting people, devoted to sermons and strict sabbath observance, to Bible-reading and psalm-singing. They would be marked by concord, their behaviour and conversation defined by rigorous disciplinary guidelines to reflect their gratitude for divine election. Their families would be well-regulated, their children literate and biblically informed, their poor nurtured.

The Reformation thus understood was a parochial endeavour, one whose outcome can only be understood by close examination of what went on in parish and pew. The political shifts of the 1550s and the ensuing civil wars would be necessary for the converted clergy to pursue their aim, but the arena where religious Reformation would happen (or not) was local and lay. Ordinary people and their lived experience of religion must therefore be the focus of students who would fully understand the Scottish Reformation.

The immediate outcome at that popular level was, of course, uneven. The Reformers’ agenda was impossibly ambitious: they must have known that fornicators, drunkards, and quarrellers would be, like the poor, always with us. But the strength of their efforts in the parishes, and their effects on Scottish culture, are undeniable. This is not because of any extraordinary power on the part of the early modern state to enforce its will, or even because protestant preachers of the first generation were either very numerous or (with a few exceptions) particularly charismatic. The authority of the Scottish crown was notoriously weak and decentralised in the sixteenth century by comparison to that of its neighbour to the south, and a preaching clergy was initially thin on the ground: a 1574 account lists only 289 ministers in 988 parishes. The relative success of the Scottish Reformation was rather because key lay people in the parishes seized upon the new religion, negotiated its terms for their own purposes, and cooperated actively in implementing its objectives in their communities.

Lay collaboration was in turn a function of the Calvinist Reformation’s particular ecclesiastical polity. The Reformers introduced to Scotland in 1560 the system that had so impressed them as exiles in Geneva, government of the church by a network of local courts comprised of lay elders along with ministers. The consistory of Geneva and the Huguenots, called the ‘kirk session’ in Scotland, was composed of the minister or ministers of a town, together with a group (generally a dozen or so in Scotland) of lay elders chosen from among the most ‘honest and famous men’ of the vicinity. These were, in a Scottish burgh, the wealthiest and most politically powerful merchants, craftsmen, and sometimes professionals like notaries, lawyers, or schoolmasters. In urban parishes, ‘landwart’ elders would eventually be added to represent the suburbs and rural areas surrounding the town that were not already subsumed by other parishes. These men were lairds, or landed gentlemen, rather than lords, so that the sessions represented a broad swath of Scottish society’s commonalty. Sessions were first established in towns, naturally enough, given their urban continental models; by the second generation after the Reformation, their structures and procedures had spread to rural areas.

Scottish kirk sessions had numerous functions, both disciplinary and administrative. Of central importance for historians of parochial religion, they kept written records of their proceedings – for which historians of religion in the pew must be eternally grateful. Surviving session minute books provide an extraordinary resource for those who seek to understand how lay people received the Reformers’ message and adapted it for their own communal purposes. In the minute books we hear the voices of ordinary folk, ranging from well-off merchants and craftsmen to servants and beggars. Women as well as men gave testimony to the session. Indeed, nearly everyone in the community would at some point in their lives appear before the session, if only to ask that their marriage banns be pronounced. The minutes report all sorts of ecclesiastical business. They illumine worship and celebration of the sacraments; catechism and doctrinal examination; church and hospital fabric; provision for schools, preachers, and readers. And given the breadth of disciplinary cases the elders heard, their records tell us no less about early modern Scottish society and culture than about religion. We hear from their minutes about childhood and old age, lax parents and abusive spouses, assault and rape, the ravages of plague and the terror of earthquake, the adventures of mariners, the work of folk healers and the desperation of their patients, neighbourhood quarrels and gossip, attitudes towards Gaelic Highlanders, the delights of sports and dancing to pipes – in short, the myriad pleasures and pains of early modern life. A well-kept session book is an historian’s treasure-trove.

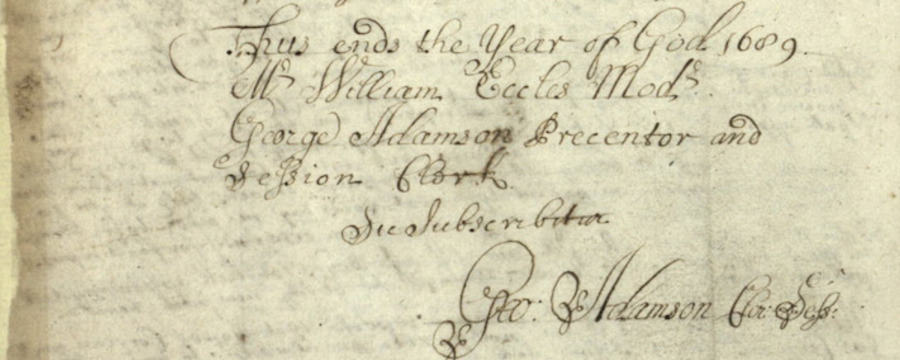

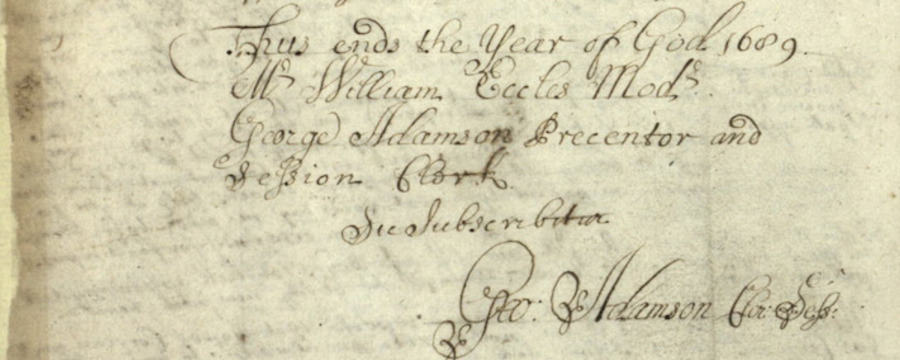

The Manuscript

The session minutes of Perth are particularly well-kept. They are among the earliest, fullest, and most continuous of the first century after the Reformation. The first extant volume, presented here along with half of the second volume, begins in May of 1577 and continues through June of 1586. It includes references to earlier, missing volumes, fragments of which can be found in the parish registers for the 1560s: these 1567–70 entries are transcribed in Appendix III to this edition. The first forty-five folios of the surviving second volume are also presented here, bringing us through 1590 and allowing some of the more salient stories begun in the first volume to reach their conclusions. The surviving minute books for this parish run through nine volumes altogether with detailed entries and few substantial gaps to 1637. The gaps are at 1613–14 and 1624–30, and the volumes beginning in January of 1615 and January of 1631 indicate continuation from volumes no longer extant, so these are survival gaps, not lapses by the session clerks. In June of 1637, a new clerk replaced the notary John Davidson, who had continued the sixteenth-century tradition of very full entries for a wide variety of business; unfortunately, the new scribe dramatically changed the nature and usefulness of the remainder of the volume, making it a sporadic and sparse listing of almost exclusively sexual cases, marriage contracts, accounts and penitents received. His records continue through March of 1642, but he neglected to record the offences of most of the penitents fisted, or the details of the sexual cases and the prescribed repentances, perhaps moving them to another book along with the plethora of other kinds of business that had occupied the court (including communion arrangements, examinations, investigations of charming, hospital and school administration, and reconciliation of quarrels). Other than a brief notation about hospital business for January 1648 on the final folio of this ninth volume, session records during the upheaval from 1642 to 1665 do not survive.10 Perth’s session books, written in secretary hand and in Scots, are deposited in the National Archives of Scotland and have been scanned for electronic access. Several folios at the beginning and end of the first volume have naturally suffered the most damage over the centuries, with edges and corners often torn away or crumbled and the ink especially at page edges badly rubbed and sometimes moisture-damaged. Ultraviolet fight has helped to decipher some of the most faded script (quite impossible to glean from the scanned version), but it has still been necessary to record a few small bits as ‘illegible’ in this edition.

The minutes are recorded by four hands that can be identified. A 7 October 1577 entry indicates that the parish reader, Jhon Swenton, had served as session clerk for at least a year. In October of1578 Walter Cully was appointed scribe. James Smyth followed as reader and clerk in December of 1579: his initials appear thereafter in the margins on 21 March 1580, and there is an 18 March 1583 reference to an act ‘maid in Mr James Smythis time’. Finally, William Cok, who became the parish reader in February of 1582, had served as clerk from at least the previous December. All four scribes took careful and quite detailed notes and developed a system of marginalia to help them keep track of how well parishioners adhered to the sessions orders, particularly in regard to marriage and the performing of repentance. Their marginal notations appear in this edition in parentheses after the corresponding entry in the text. They should not be undervalued: for the elders they served as important bureaucratic tools and practical enforcement mechanisms in disciplinary cases.

The availability of other contemporary Perth manuscripts encouraged the decision to edit Perth’s session minutes. These help to identify named individuals, verify and further describe key events, confirm dating, and sometimes indicate the outcome of a case not fully recorded in the session minutes. Marriage registers survive from 1560 to 1582, baptismal records from 1561 to February of 1582, and burial registers from 1561 to 1581, though with significant gaps. The ‘Chronicle of Perth’, partly written before 1600 by the town clerk, among others, and now in the National Library of Scotland, includes accounts of storms, earthquakes, plague outbreaks, political events, and crimes and scandals that allow us to expand on brief allusions in the session minutes. It is this document that gives us, for instance, the appalling tally of 1584–85 plague deaths at 1427. Minutes of the town council and the bailies courts in the Perth and Kinross Council Archives help to define the context in which the session operated – hand in glove with the magistracy – and to identify the overlapping personnel of the burgh and ecclesiastical courts. In the same archive is an assortment of decreet books, registers of acts and obligations, caution rolls, and accounts (including those related to ministerial stipends and hospital properties) which aid in identifying people and again in setting the context in which the elders operated. Of inestimable value have been the surviving records of the mercantile guildry (from 1452 to 1601) and five crafts guilds. The ‘Guildrie Book’ is still in the hands of the Perth Guildry Incorporation, but has been edited and published. The National Library of Scodand holds the hammermen s book, and the Perth and Kinross County Archives keep the glovers’ and baxters’ books. The records of the tailors and wrights are in the Perth Museum and Art Gallery. These allow identifications, but they also suggest that secular models for record-keeping and disciplinary activity may well have inspired some of the session’s conventions. Notarial protocol books, in particular those of Henry Elder and his son, have filled in some gaps. The published ‘Rental Books of King James VI Hospital’, together with manuscript hospital documents in the National Archives, illumine the session’s oversight of poor relief. Records of the Justiciary Court and the Court of Session in the West Register House of the National Archives have allowed tracking of some particularly serious cases, as have the divorce decrees in the Commissary Court. Finally, many Perth wills survive from the 1570s and 1580s in the Commissary Courts of Edinburgh and St Andrews. These have been very helpful in identifying propertied individuals mentioned in the session book, particularly the elders, who are listed in Appendix I.

An unusual collection of rather later manuscripts has also proven useful in the editorial process. An eighteenth-century minister of Perth and avid antiquarian, James Scott, wrote out excerpts from the sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Perth religious records of all sorts, including session volumes. His notebooks are now in the Advocates Collection of the National Library. The first volume copied from the session books has occasionally come in handy when deciphering the more puzzling parts of the manuscript; however, Scott’s transcription is by no means reliable. Even if it were complete, rather than just his favourite portions, he mis-dated entries, updated and sometimes mangled spellings, and made rather too many wild guesses to be altogether trustworthy. His notebooks are, however, abundantly annotated, and despite his obvious religious biases, these notes have been of some help; they will accordingly appear in the notes in this volume where appropriate.

A final reason for selecting Perth’s session book to edit is the importance of the town itself to the history of early modern Scotland. Perth was one of the ‘four great burghs’ of the sixteenth century (with Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee). It occupied a central place in the early history of the Reformation, in the political history of James VI’s early reign, and eventually in the story of the civil wars of the 1640s and the Cromwellian invasion.

Extract taken from Margo Todd (ed), The Perth Kirk Session Records, Sixth Series, Vol. 2 (Scottish History Society, 2012), pp. 1–8.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free