Text Chapters 25 – 27

CHAPTER XXV THE PRINCESS PURSUES HER INQUIRY WITH MORE DILIGENCE THAN SUCCESS.

The Princess in the meantime insinuated herself into many families; for there are few doors through which liberality, joined with good humour, cannot find its way. The daughters of many houses were airy and cheerful; but Nekayah had been too long accustomed to the conversation of Imlac and her brother to be much pleased with childish levity and prattle which had no meaning. She found their thoughts narrow, their wishes low, and their merriment often artificial. Their pleasures, poor as they were, could not be preserved pure, but were embittered by petty competitions and worthless emulation. They were always jealous of the beauty of each other, of a quality to which solicitude can add nothing, and from which detraction can take nothing away. Many were in love with triflers like themselves, and many fancied that they were in love when in truth they were only idle. Their affection was not fixed on sense or virtue, and therefore seldom ended but in vexation. Their grief, however, like their joy, was transient; everything floated in their mind unconnected with the past or future, so that one desire easily gave way to another, as a second stone, cast into the water, effaces and confounds the circles of the first.

With these girls she played as with inoffensive animals, and found them proud of her countenance and weary of her company.

But her purpose was to examine more deeply, and her affability easily persuaded the hearts that were swelling with sorrow to discharge their secrets in her ear, and those whom hope flattered or prosperity delighted often courted her to partake their pleasure.

The Princess and her brother commonly met in the evening in a private summerhouse on the banks of the Nile, and related to each other the occurrences of the day. As they were sitting together the Princess cast her eyes upon the river that flowed before her. “Answer,” said she, “great father of waters, thou that rollest thy goods through eighty nations, to the invocations of the daughter of thy native king. Tell me if thou waterest through all thy course a single habitation from which thou dost not hear the murmurs of complaint.”

“You are then,” said Rasselas, “not more successful in private houses than I have been in Courts.” “I have, since the last partition of our provinces,” said the Princess, “enabled myself to enter familiarly into many families, where there was the fairest show of prosperity and peace, and know not one house that is not haunted by some fury that destroys their quiet.

“I did not seek ease among the poor, because I concluded that there it could not be found. But I saw many poor whom I had supposed to live in affluence. Poverty has in large cities very different appearances. It is often concealed in splendour and often in extravagance. It is the care of a very great part of mankind to conceal their indigence from the rest. They support themselves by temporary expedients, and every day is lost in contriving for the morrow.

“This, however, was an evil which, though frequent, I saw with less pain, because I could relieve it. Yet some have refused my bounties; more offended with my quickness to detect their wants than pleased with my readiness to succour them; and others, whose exigencies compelled them to admit my kindness, have never been able to forgive their benefactress. Many, however, have been sincerely grateful without the ostentation of gratitude or the hope of other favours.”

CHAPTER XXVI THE PRINCESS CONTINUES HER REMARKS UPON PRIVATE LIFE.

Nekayah, perceiving her brother’s attention fixed, proceeded in her narrative.

“In families where there is or is not poverty there is commonly discord. If a kingdom be, as Imlac tells us, a great family, a family likewise is a little kingdom, torn with factions and exposed to revolutions. An unpractised observer expects the love of parents and children to be constant and equal. But this kindness seldom continues beyond the years of infancy; in a short time the children become rivals to their parents. Benefits are allowed by reproaches, and gratitude debased by envy.

“Parents and children seldom act in concert; each child endeavours to appropriate the esteem or the fondness of the parents; and the parents, with yet less temptation, betray each other to their children. Thus, some place their confidence in the father and some in the mother, and by degrees the house is filled with artifices and feuds.

“The opinions of children and parents, of the young and the old, are naturally opposite, by the contrary effects of hope and despondency, of expectation and experience, without crime or folly on either side. The colours of life in youth and age appear different, as the face of Nature in spring and winter. And how can children credit the assertions of parents which their own eyes show them to be false?

“Few parents act in such a manner as much to enforce their maxims by the credit of their lives. The old man trusts wholly to slow contrivance and gradual progression; the youth expects to force his way by genius, vigour, and precipitance. The old man pays regard to riches, and the youth reverences virtue. The old man deifies prudence; the youth commits himself to magnanimity and chance. The young man, who intends no ill, believes that none is intended, and therefore acts with openness and candour; but his father; having suffered the injuries of fraud, is impelled to suspect and too often allured to practise it. Age looks with anger on the temerity of youth, and youth with contempt on the scrupulosity of age. Thus parents and children for the greatest part live on to love less and less; and if those whom Nature has thus closely united are the torments of each other, where shall we look for tenderness and consolations?”

“Surely,” said the Prince, “you must have been unfortunate in your choice of acquaintance. I am unwilling to believe that the most tender of all relations is thus impeded in its effects by natural necessity.”

“Domestic discord,” answered she, “is not inevitably and fatally necessary, but yet it is not easily avoided. We seldom see that a whole family is virtuous; the good and the evil cannot well agree, and the evil can yet less agree with one another. Even the virtuous fall sometimes to variance, when their virtues are of different kinds and tending to extremes. In general, those parents have most reverence who most deserve it, for he that lives well cannot be despised.

“Many other evils infest private life. Some are the slaves of servants whom they have trusted with their affairs. Some are kept in continual anxiety by the caprice of rich relations, whom they cannot please and dare not offend. Some husbands are imperious and some wives perverse, and, as it is always more easy to do evil than good, though the wisdom or virtue of one can very rarely make many happy, the folly or vice of one makes many miserable.”

“If such be the general effect of marriage,” said the Prince, “I shall for the future think it dangerous to connect my interest with that of another, lest I should be unhappy by my partner’s fault.”

“I have met,” said the Princess, “with many who live single for that reason, but I never found that their prudence ought to raise envy. They dream away their time without friendship, without fondness, and are driven to rid themselves of the day, for which they have no use, by childish amusements or vicious delights. They act as beings under the constant sense of some known inferiority that fills their minds with rancour and their tongues with censure. They are peevish at home and malevolent abroad, and, as the outlaws of human nature, make it their business and their pleasure to disturb that society which debars them from its privileges. To live without feeling or exciting sympathy, to be fortunate without adding to the felicity of others, or afflicted without tasting the balm of pity, is a state more gloomy than solitude; it is not retreat but exclusion from mankind. Marriage has many pains, but celibacy has no pleasures.”

“What then is to be done?” said Rasselas. “The more we inquire the less we can resolve. Surely he is most likely to please himself that has no other inclination to regard.”

CHAPTER XXVII DISQUISITION UPON GREATNESS.

The conversation had a short pause. The Prince, having considered his sister’s observation, told her that she had surveyed life with prejudice and supposed misery where she did not find it. “Your narrative,” says he, “throws yet a darker gloom upon the prospects of futurity. The predictions of Imlac were but faint sketches of the evils painted by Nekayah. I have been lately convinced that quiet is not the daughter of grandeur or of power; that her presence is not to be bought by wealth nor enforced by conquest. It is evident that as any man acts in a wider compass he must be more exposed to opposition from enmity or miscarriage from chance. Whoever has many to please or to govern must use the ministry of many agents, some of whom will be wicked and some ignorant, by some he will be misled and by others betrayed. If he gratifies one he will offend another; those that are not favoured will think themselves injured, and since favours can be conferred but upon few the greater number will be always discontented.”

“The discontent,” said the Princess, “which is thus unreasonable, I hope that I shall always have spirit to despise and you power to repress.”

“Discontent,” answered Rasselas, “will not always be without reason under the most just and vigilant administration of public affairs. None, however attentive, can always discover that merit which indigence or faction may happen to obscure, and none, however powerful, can always reward it. Yet he that sees inferior desert advanced above him will naturally impute that preference to partiality or caprice, and indeed it can scarcely be hoped that any man, however magnanimous by Nature or exalted by condition, will be able to persist for ever in fixed and inexorable justice of distribution; he will sometimes indulge his own affections and sometimes those of his favourites; he will permit some to please him who can never serve him; he will discover in those whom he loves qualities which in reality they do not possess, and to those from whom he receives pleasure he will in his turn endeavour to give it. Thus will recommendations sometimes prevail which were purchased by money or by the more destructive bribery of flattery and servility.

“He that hath much to do will do something wrong, and of that wrong must suffer the consequences, and if it were possible that he should always act rightly, yet, when such numbers are to judge of his conduct, the bad will censure and obstruct him by malevolence and the good sometimes by mistake.

“The highest stations cannot therefore hope to be the abodes of happiness, which I would willingly believe to have fled from thrones and palaces to seats of humble privacy and placid obscurity. For what can hinder the satisfaction or intercept the expectations of him whose abilities are adequate to his employments, who sees with his own eyes the whole circuit of his influence, who chooses by his own knowledge all whom he trusts, and whom none are tempted to deceive by hope or fear? Surely he has nothing to do but to love and to be loved; to be virtuous and to be happy.”

“Whether perfect happiness would be procured by perfect goodness,” said Nekayah, “this world will never afford an opportunity of deciding. But this, at least, may be maintained, that we do not always find visible happiness in proportion to visible virtue. All natural and almost all political evils are incident alike to the bad and good; they are confounded in the misery of a famine, and not much distinguished in the fury of a faction; they sink together in a tempest and are driven together from their country by invaders. All that virtue can afford is quietness of conscience and a steady prospect of a happier state; this may enable us to endure calamity with patience, but remember that patience must oppose pain.”

Share this

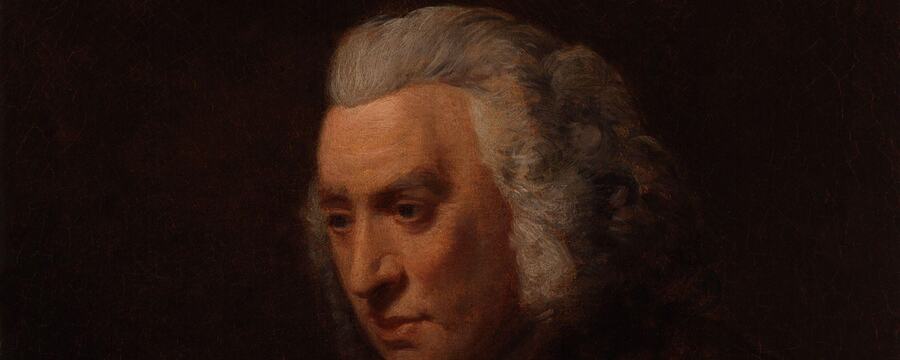

Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas: An Introduction

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free