History of Japan: When Did Reading as Education Begin?

Share this step

With the introduction of movable type printing in the early Edo period, books began to be printed in large quantities and to reach a wide audience. A much wider section of society now had access to books compared to medieval times, with obvious consequences on the spread of knowledge and education.

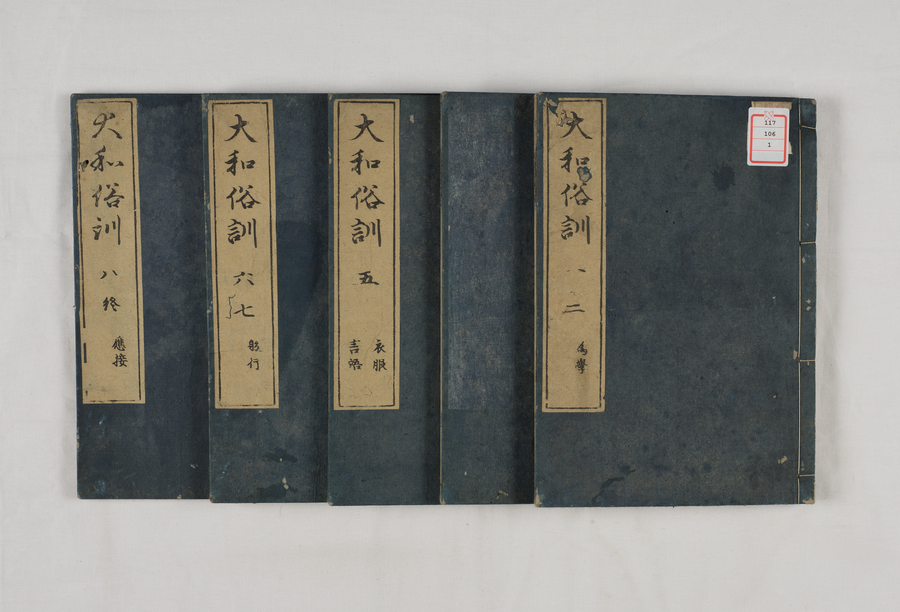

To begin, let us look at the Yamato zokkun (Precepts for Daily Life in Japan) (Fig.1), published in 1708 by Kaibara Ekken (1630-1714), a scholar from the Fukuoka domain.

Fig.1. Yamato zokkun, Kaibara Ekken, 1708 edition.

Fig.1. Yamato zokkun, Kaibara Ekken, 1708 edition.

Bottom Left: Passage quoted below.

Click to take a closer look

The book belongs to the genre of the so-called self-improvement books and explains in plain Japanese “how life should be lived”. Regarding “how to study” (ika ni manabu ka), the author notes:

博く学ぶの道は、見ると聞くとの二をつとむ。聖賢の書をよみ、人に道をききて、古今を考へて道理を求むるなり。 (中略) 博く学ぶの道多けれど、書をよむほど益あるはなし。古人も人の知恵をますは、書にしくはなしといへり。されど文字をのみ好みて、義理を求めざるは博く学ぶにはあらず。[English translation] In order to acquire a broad education, you must both look and listen. That is to say, you must read the works of the sages, learn about your subject from teachers,and seek to understand the nature of things by pondering past and present events. [ … ] There are many ways to learn, but none is more valuable than reading books. As the people of the past used to say, nothing is better than books to expand your knowledge. However, if you only read books and do not aim to understand the principle of rightness, you will never acquire a broad education.

Ekken distinguishes two main study methods: one is reading, that is, learning through and from books; the other is listening, that is, learning from a teacher. Both are necessary, but Ekken seems to be asserting that reading is the primary one.

Ekken was a Confucian scholar and when he says books what he probably had in mind is the Chinese classics, starting with Confucius’Analects (J. Rongo). Yet, as noted earlier, the Yamato zokkun is written in plain, easy to understand Japanese and was directed at a less educated audience, so his remarks about how to study are not aimed only to an erudite audience but to everyone. The pedagogic value of books had been recognized long before the Edo period, but it is only in the Edo period, when books become a mass commodity, that we see their importance so publicly advertised in a book for the general public.

Booksellers

So to what extent had books penetrated Japanese society when the Yamato zokkun was published? One way to answer the question is to look at the number of bookshops present in Japanese cities at the time.

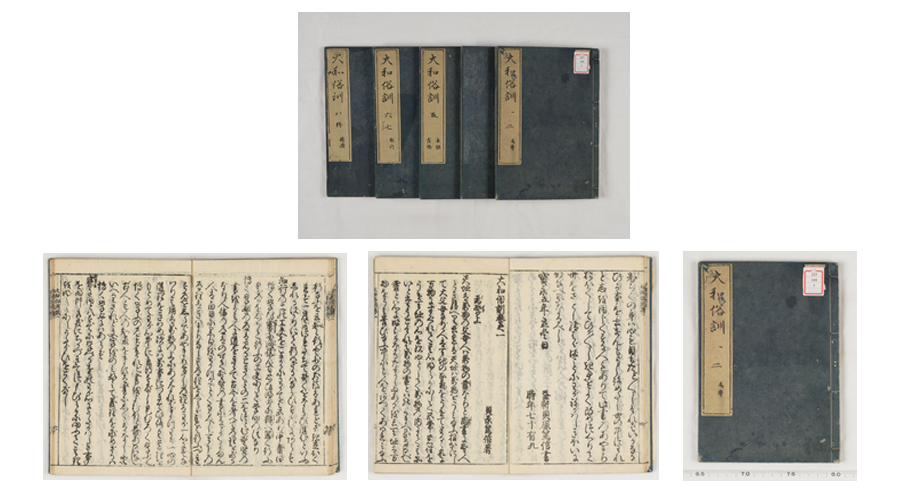

Fig.2. Yorozu kaimono chōhōki, 1692.

Fig.2. Yorozu kaimono chōhōki, 1692.

From the top: cover, page44, page 45, page46, page47

Click to take a closer look

The book shown here (Fig.2) is the Yorozu kaimono chōhōki, (A Guide to Shopping of All Kinds), which lists the trading establishments in the three major cities of the time (Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka). The section on bookshops gives us an idea of how many establishments were in existence in the late 17th century. Bookshops are grouped by the type of books they sold. Under the “Poetry Books and Illustrated books” category, we find shops that dealt with poetry-related and popular, entertainment books. It lists the names of three shops in Kyoto, five shops in Edo, and three in Osaka (page 44). Another category is “Scholarly Bookshops” which lists shops that specialized in highbrow content such as the Confucian classics, Buddhist works, and medicine. 11 shops in Kyoto, 27 in Edo, and 23 in Osaka are listed (page 45), including shops specializing in both new and second-hand items. Under “Chinese books,” we find shops that specialized in imported books from China(page 46), whereas the category “Theater books” lists shops dealing in drama-related books (page 46) (page 47). Needless to say, the lists are selective and do not mention each and every establishment in operation at the time.

Temple Schools

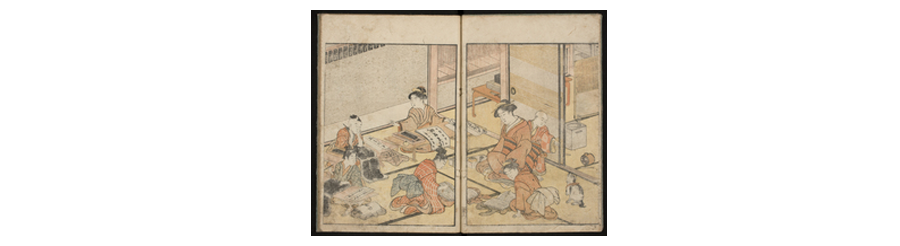

The late 18th century Ehon sakaegusa (Fig.3), an illustrated book by the artist Katsukawa Shunchō, shows us what contemporary temple schools (known as terakoya) looked like.

Fig.3. Ehon sakaegusa (Leaves of Prosperity), “Learning to write”, Katsukawa Shunchō, 1790

Fig.3. Ehon sakaegusa (Leaves of Prosperity), “Learning to write”, Katsukawa Shunchō, 1790

(Click to take a closer look)

On left-hand side of the picture, we see two children sitting at the desk holding a brush and practicing writing. In Edo times, “learning to write” (tenarai) consisted of repeatedly copying words and sentences from a copybook. To save paper, every inch of the sheet has been used so that the sheet is completely covered in black ink. On the right-hand side, there is a female teacher holding a baby on her back and two little girls sitting in front of her with an open book in front of them. They point at the characters on the page with a stick. The girls are actually learning to recite Chinese texts in Chinese by mimicking the teacher’s pronunciation. The stick they are holding was called a jisashi (character pointer), and was used to trace the lines of the characters as one read them. In learning to both read and write, “repetition” was the key pedagogic device, and texts were an indispensable tool in both cases.

Temple schools were the simplest way for commoners to acquire the basic skills needed in everyday life (literacy, arithmetic, etc.). Over the course of the Edo period, thousands of books for use as textbooks in temple schools were published.

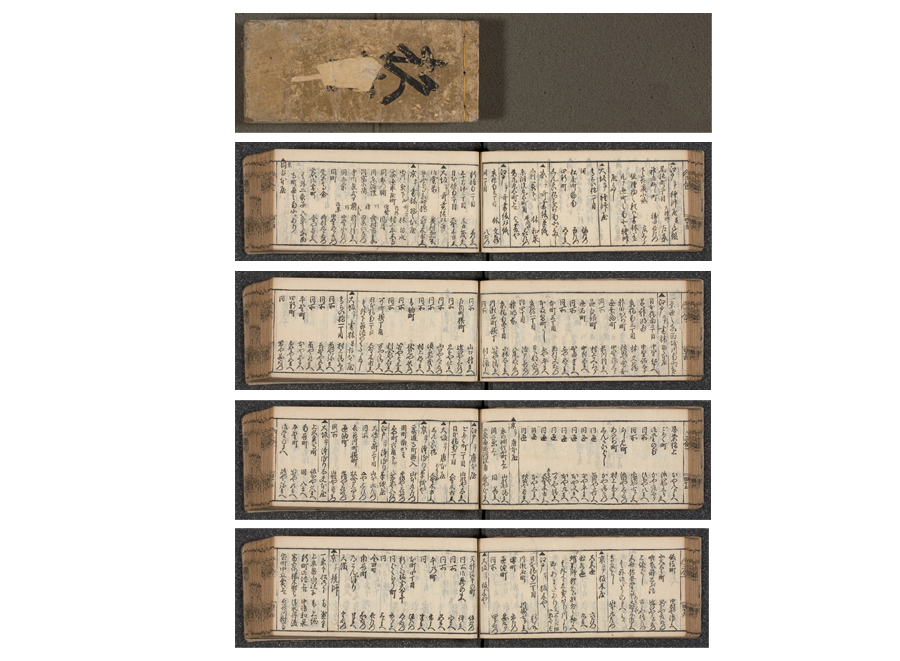

Fig.4. Ehon teikin ōrai (Illustrated Book of Domestic Manners), illustrated by Katsushika Hokusai (19th c.).

Fig.4. Ehon teikin ōrai (Illustrated Book of Domestic Manners), illustrated by Katsushika Hokusai (19th c.).

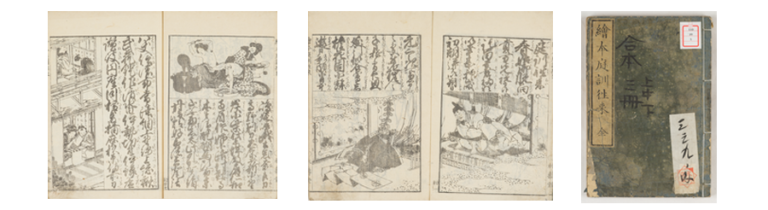

Left: beginning of the text, Center: image of the temple school, Right: cover

Click to take a closer look

One example is the Ehon teikin ōrai (Fig.4). Because the illustrations are by the famous painter and printmaker Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), they are larger than usual. One of them shows students at work at a temple school.

Fig.5. Onna daigaku (The Great Learning for Women), Kaibara Ekken,1844

Fig.5. Onna daigaku (The Great Learning for Women), Kaibara Ekken,1844

Click to take a closer look

Onna daigaku (Fig.5), a popular behavior manual for women, contains an image of young girls learning to read Chinese texts from a female instructor. Images of commoners learning from books are indeed common in Edo-period educational books.

Despite some obvious changes, attitudes to education remained rather consistent after the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the beginning of the Meiji period.

Fig.6. Kinsei onna daigaku (The Modern Great Learning for Women), Doi Kōka,1874.

Fig.6. Kinsei onna daigaku (The Modern Great Learning for Women), Doi Kōka,1874.

Right: Opening slogan “Equal Rights for Men and Women”

Click to take a closer look

With the influx of ideas and institutions from the West following the Restoration, Japan rapidly reorganized itself as a modern nation state. As the title shows, Doi Kōka (1847-1918)’s Kinsei onna daigaku (Fig.6) was conceived as a “Great Learning for Women” for the modern age. The slogan “Equal rights for men and women, two partners one household” is printed in large letters on the cover. In keeping with the slogan, one of the front illustrations, by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889), shows two couples of husbands and wives, one Japanese and one Western, each dressed in their usual attire. Another (Western-style) illustration, shows a stern-looking (Western) teacher addressing a classroom of Western female students with the words “Attention all!” Two years before Kinsei onna daigaku was published, in 1872, Japan had just introduced a modern, centralized national education system and Doi’s book reflects the ideas and values of this new age. At the same time, it clearly follows in the tradition of Edo-period pedagogic books with their emphasis on reading for women.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free