Interview with a United Nations photographer

Share this step

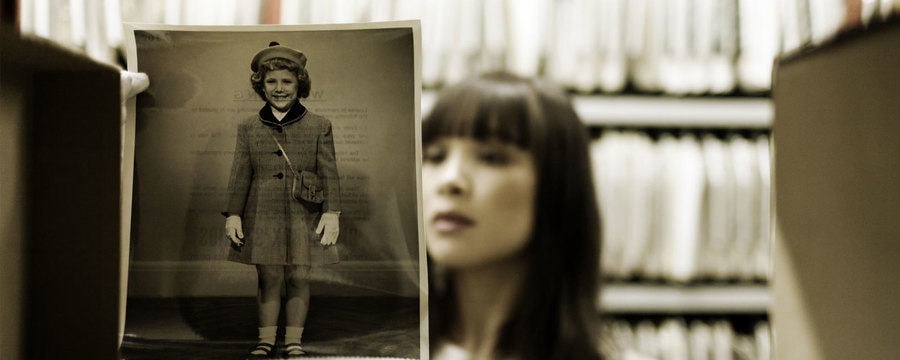

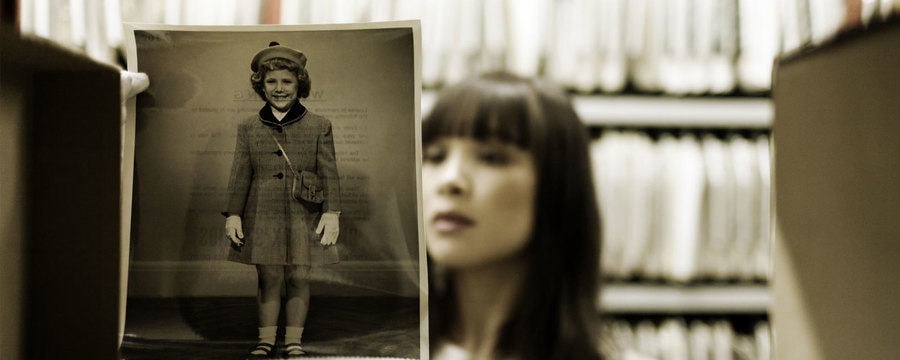

In this interview, Maiken Umbach is asking Nerris Markogiannis, the United Nations photographer we encountered in the previous learning step, some questions about his professional practice. We have already discussed the way victims have been photographed in various historical moments. Is there a lesson we can learn from this history, and take and view photos differently?

1. Maiken: We are used to seeing shocking photographs in the media. We see photos of people suffering everywhere: photos designed to inform us, and to mobilize our sympathy, perhaps even our financial support, for people facing a humanitarian emergency or crisis. As a professional photographer working for the UN, you’ve recorded images of people who are the victims of many different crises. Is there a danger that photos of victims are themselves becoming a cliché, which renders the specificity of each situation, and each individual’s experience, effectively invisible?

Nerris: Certain employers have specific requirements. They need clichéd images of either pain and suffering or happiness. The cliché predates the situation. While photographing pain, misery and famine, the product is designed to appeal emotionally to viewers, and connect them with subjects in a particular way. The idea behind those images is that someone is suffering and we should be sympathetic and do something about it. Usually these images don’t succeed in mobilizing people to help. Most people think/hope/believe that action to alleviate misery and poverty will come from the outside… as if there will be a sort of metaphysical intervention. And while the average viewer hopes for an intervention, photojournalists continue to replicate stereotypes in Africa (and elsewhere, I think there is a stereotype for much for the ‘Third World’. I am using Africa as my example because I have spent two thirds of my UN career in Africa). Malnourished children, either alone and pensive or with their mothers continue to be favourite subjects. One way to escape from stereotypes is to aestheticize our images.

Most people see parts of the so called Third World (like Africa, Asia, and certain parts of Latin America and the Middle East) either as places of human misery, or as exotic places. The visual story we need to tell about these places is not a single story. We need a series of stories, which when put together, will help us end the idea of a singular Africa, Asia or any other part of the world.

Let me give you an example from my work and personal experience. We receive requests from the media, mostly international media (newspapers, wire services, news channels), and what we do is that we take these journalist to the places we feel more comfortable at. These places are the Camps for Displaced People, or Protection of Civilian Camps, if protection is an issue too. The next thing you know is that you will see hard images of starving children in newspapers and magazine articles. Surely these images reinforce stereotypes. This might seem normal to you, but to me, this is the equivalent of photographing homeless people outside King’s Cross station and claiming that “this is London”. But no, it won’t work, because our stereotype of London is not that of homeless people. The ease with which we can accept stereotypes about others is remarkable. But when it comes to the representation of our own world, we would not accept a singular representation, especially not the one of the homeless people as been the universal image of London (you can replace London with NY, Tokyo, Paris, Berlin, etc).

2. Maiken: As a photographer, what control do you have about how your photos are used? Your images have been published widely in the media. Who makes the decisions about which images are selected, and which are not? Who writes the captions, and the accompanying text – do they, in your experience, help to elucidate the meaning of your images, or can you think of examples where texts interpreted your photos differently from how you intended them?

Nerris: Working for the United Nations, my control over the photos I take kind of ends the moment I post them on line. We use a professional FLICKR account to create albums from the mission’s activities [You can find the link to the page below this step]. Once I come back from an assignment, I am solely responsible for editing the images. I have the freedom to select which photos are to be published and which are not, either because they are not good enough, or because they might be sensitive and potentially damaging. After I select the number and kind of pictures I will publish, I write the captions. I usually write the caption myself. If the event I am covering is politically sensitive, then I sit down with people from UN sections like Political Affairs, or Security, or Human Rights, and we write the captions together. However, I don’t have control how others use my photos, and in what context. UN Photos are free to use, as long as one gives credit to the UN mission and the photographer. Usually the caption, if written by someone other than me, is a dry reference to the event which the photo is related. I remember one case where one of my photos from Kosovo was used by someone on his personal blog, in a piece which was openly biased towards one of the conflicting sides. It did not necessarily change the meaning or context of my image, in the sense that it was demonstrating nationalistic tendencies. I was unhappy that the blogger chose my photo.

In general, and I think that this comes with experience, I select images for my story that cannot be interpreted in any other way than the one I meant to. I also try to photograph in a way that won’t allow alterations like cropping. This is an attempt to exercise some control over my images. I regularly google my name, and try to see who is using my images and in what context.

3. Maiken: Can you talk us through a a specific example of a photo you have taken and its “back story”? What inspired you to take this specific image? What specifically about the situation you witnessed did you want to capture?

Nerris: This photograph of a mother with her teenage daughter was taken in February 2009. I took it inside a UN military helicopter, used to evacuate the mother and daughter. This was after the village of Wadda was attacked, allegedly by rogue elements allied with the government of Sudan. For those who haven’t been inside a military helicopter: there are two rows of seats (approximately 10 each) on each side. The space in between is usually used for cargo. On this day, there wasn’t any cargo. Instead, we set up a place for the mother to sit, and her daughter (who was injured) to lie down. The woman is not looking at me taking the photo; she is staring at the cockpit’s door. She is one of the few survivors of the attack. Her whole family perished, husband and children. She and her injured daughter were the only survivors. I was sitting on the left of the woman. I couldn’t help noticing that she was totally lost. For a moment, I tried to imagine what might was going on inside her head. I doubted that she has ever left her village before, doubted she has even be inside any sort of vehicle. And here she is now, inside a helicopter. She and her daughter were being evacuated, and they had no idea where they were taken to, and what was going to happen to them.

In the background one can notice two soldiers. These are United Nations’ peacekeepers taking a ride back to El Fasher, the capital of Darfur, after having responded to the emergency situation in Wadda. One cannot miss the expression on the soldiers’ faces.

All I had to do was to just move in front of her and take the picture. She didn’t blink an eye. Did she even realize that I was taking a photo?

The physical beauty of this woman combined with the completely lost and empty look on her face, but also what I knew happened to her and her family, moved me to take the photo. All I wanted to capture was the look on the face of someone who has lost everything, and has not idea what lies ahead.

4. Maiken: What about the agency of those who are being photographed? What can you, as a photographer, do to record stories and experiences in ways that reflect the perspective of those whom you are photographing?

Nerris: As photographer I photograph with my whole being. The way I see the world (and I believe that’s the case for everyone) very much depends on socioeconomic, educational, and political backgrounds. But I strongly believe that we can change when we actually get to live in a country and mix with the people we are photographing. I think that living in country for a long time is different from the “participant’s observation” method used by many social scientists. Most of these scientists have a project in mind, whereas someone in my line of work doesn’t. It is true that conflicts that are found is the same geographical region (or almost the same) can have visually similar characteristics. For example, photographing in Syria, Lebanon or Gaza, can result in similar images. Photographing in Bosnia, Croatia, or Kosovo again can produce similar images. Africa is not an exception to the rule. Only if someone gets to live for prolonged periods in one place, will he or she get the opportunity to feel the struggle or the people. That said, one should not fall into the trap of sympathizing with one side or another. Spending too much time with one people might make you identify with them, and then produce work that is biased. Appropriate training helps, as does an understanding of the conflict, its history and its dynamics. I try my best to approach my “subjects” with a clear mind, and respect. Those who are being photographed, in a strange way, can sense the photographer’s intentions. A photographer needs to feel at ease. Feel that he or she is not doing anything wrong. Invading someone’s privacy at a time of war, or conflict, or even at a post conflict situation, is not the same as doing it in a “normal set up”. At times of war or conflict, social norms as we know them cease to exist. But your subject needs to feel, feel that it is okay to trust you and open up. Then we, as photographers, can photograph them in a way that reflects their perspective of the story.

The ability to tell someone’s story from his or her point of view also comes with experience. One photographer who has mastered this is the Brazilian born Sebastiao Salgado. Eduardo Galeano, an important literary figure from Uruguay, wrote an essay on Salgado. It appeared in the catalogue of Salgado’s exhibition in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In this, Galeano argues that while “Salgado photographs people, casual photographers photograph phantoms”. He continues:

“As an article of consumption, poverty is a source of morbid pleasure and much money. Poverty is a commodity that fetches a high price on the luxury market. Consumer society’s photographers approach but do not enter. In hurried visits to scenes of despair or violence, they climb out of the plane or helicopters, press the shutter release, explode the flash, they shoot and run. They have looked without seeing, and their images say nothing. Their cowardly photographs soiled with horror or blood may extract a few crocodile tears, a few coins, a pious word or two from the privileged of the earth, none of which changes the order of their universe.“ He concludes: “Charity, vertical, humiliates. Solidarity, horizontal, helps. Salgado photographs from inside, in solidarity”.

In the discussion, we’d love to hear your responses to Nerris’s reflections on his own work. Does it make you look differently at similar photos you may have seen in the press? And does it change your view of what makes for a “good”, or “appropriate”, photos of people faced with existential crises?

Further Resources:

The online photo account of the UN Mission that Nerris mentions in the interview can be accessed here:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/unmissmultimedia/

More of Nerris’s own photographic work can be viewed here:

http://ny-photography-diary.com/sebastiao-salgado-by-nerris-markogiannis/

and here:

https://www.instagram.com/nerrismarkogiannis/?hl=en

Share this

Learning from the Past: A Guide for the Curious Researcher

Learning from the Past: A Guide for the Curious Researcher

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free