Home / History / British History / History of Slavery in the British Caribbean / Slave Codes: The Legalisation of Racialised Violence

This article is from the free online

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

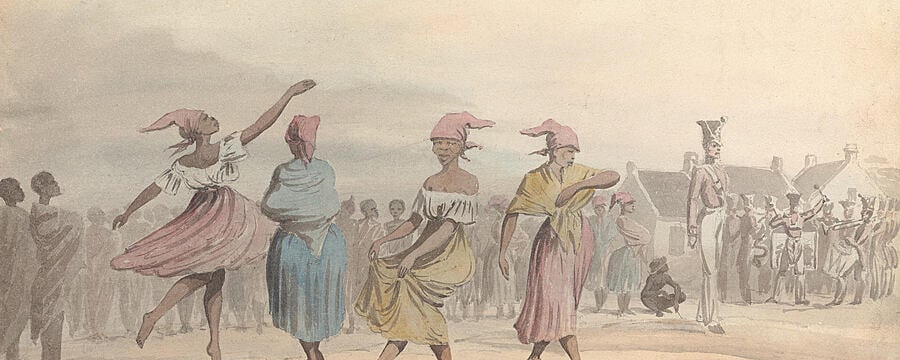

Augustus Earle, ‘Slave market at Rio Janeiro’, Longman & Co. & J. Murray, 1824. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Augustus Earle, ‘Slave market at Rio Janeiro’, Longman & Co. & J. Murray, 1824. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

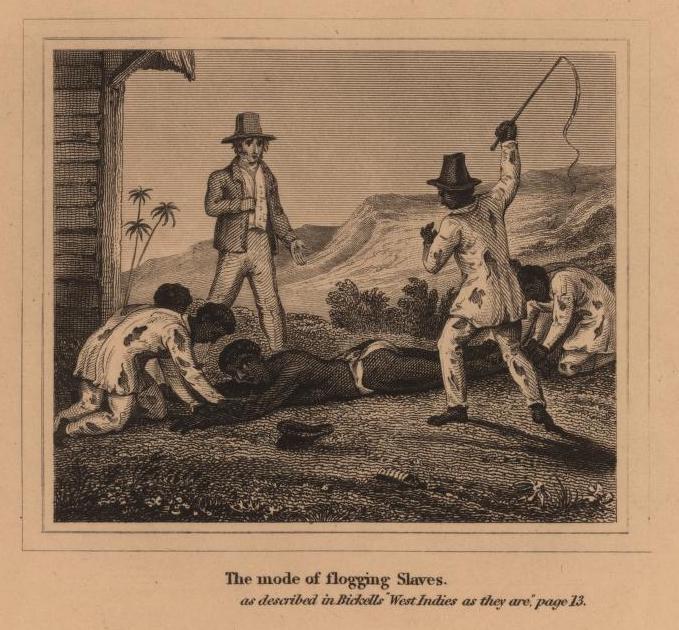

‘The mode of flogging Slaves.’ The Birmingham Female Society for the relief of British negro slaves, Benjamin Hudson, Bull Street, Birmingham, 1828. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library

‘The mode of flogging Slaves.’ The Birmingham Female Society for the relief of British negro slaves, Benjamin Hudson, Bull Street, Birmingham, 1828. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library

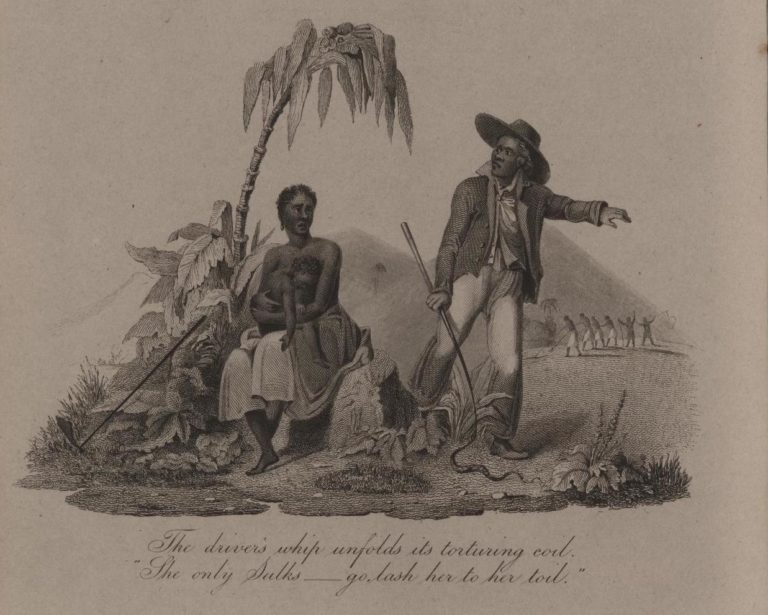

‘The driver’s whip unfolds its torturing coil. “She only Sulks–go, lash her to her toil.”.’ The Birmingham Female Society for the relief of British negro slaves, Benjamin Hudson, Bull Street, Birmingham, 1828. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library

‘The driver’s whip unfolds its torturing coil. “She only Sulks–go, lash her to her toil.”.’ The Birmingham Female Society for the relief of British negro slaves, Benjamin Hudson, Bull Street, Birmingham, 1828. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library