Psychology and Sustainability: Harnessing Environmental Behaviours

Share this step

For sustainability initiatives to be successful, they need to be adopted by the people they are aimed at. This requires an understanding of individuals and groups so that resource is not wasted on new technologies and policies that fail in their implementation phases. This article looks at some of the frameworks developed to harness our attitudes and behaviours to sustainability.

Understanding the United Kingdom: The Defra (2008) framework for sustainable behaviours report

The UK government has made a number of attempts to develop an understanding of British pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours. For example, there have been periodic surveys of public perceptions of sustainable behaviours conducted by the Department for Transport, while Defra (the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) has developed a “framework for sustainable behaviours” which identifies different “segments” and top level “groups” of the population based on their attitudes and behaviours (Defra, 2008).

The Defra study concentrated on the main public consumption clusters of food and drink, personal travel, homes and household products, and travel tourism. Environmental behaviours across all the environmental sectors, including climate change, air quality, water quality, waste, biodiversity and protection of natural resources, taking account of our “global footprint”, were considered. Specifically, the study investigated 12 headline behaviour goals, selected after a process of stakeholder engagement, to identify a range of low/high impact and easy/hard behaviours some of which could potentially engage large numbers of people and others which would be more appropriate for targeting particular population groups. The 12 goals, across five sectors were:

Personal transport

1.Use more efficient vehicles

2.Use car less for short trips

3.Avoid unnecessary flights (short haul)

Homes: waste

4.Increase recycling

5.Waste less food

Homes: energy

6.Install insulation

7.Better energy management

8.Install microgeneration (the small-scale generation of electric power by individuals, small businesses and communities to meet their own needs)

Homes: water

9.More responsible water usage

Eco-products

10.Buy energy efficient products

11.Eat more food that is locally in season

12.Adopt a lower impact diet.

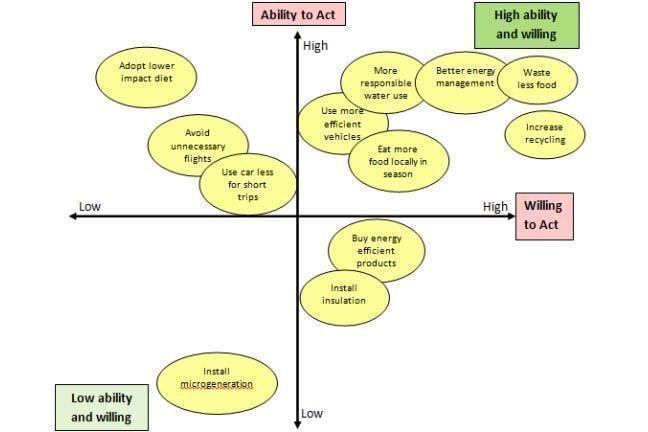

The Defra study looked at people’s willingness and ability to act on these 12 headline goals in the UK. The results showed that there are some behaviour goals to which the door is relatively open, as most people are already willing to act and have a high ability to do so. For example, to waste less food, adopt better energy management in the home, and engage in more responsible water usage. Goals that were found to be more challenging were either those where there is low ability and low willingness to act (e.g. install micro-generation) or those where willingness is low although people acknowledge that they could act (e.g. avoiding unnecessary flights). These are summarised in Figure 1 at the top of this page: People’s willingness and ability to act on 12 headline goals of sustainability.

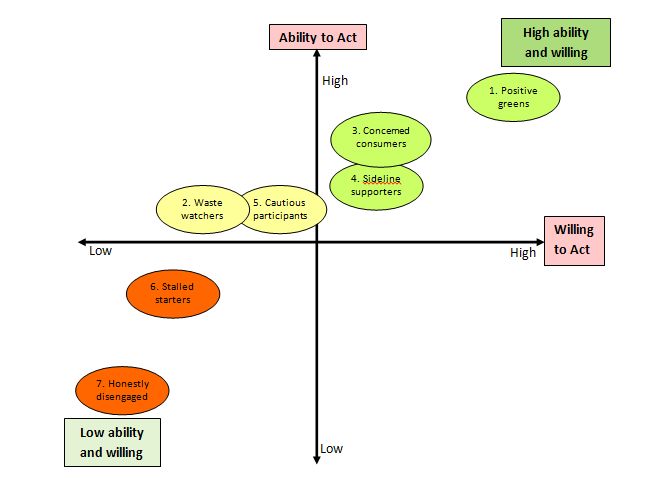

Based upon the results that Defra found, they then divided the UK population into seven broad segments. Each segment was defined by a person’s ability and willingness to act on the 12 sustainability goals. The seven segments were:

1.Positive greens

2.Waste watchers

3.Concerned consumers

4.Sideline supporters

5.Cautious participants

6.Stalled starters

7.Honestly disengaged

The seven segments are shown diagrammatically in Figure 2 below: The seven segments of the UK population based upon a person’s ability and willingness to act on the 12 sustainability goals together, as defined by Defra in the 2008 report.

Defra then divided the seven segments into three top-level groups (these are identified by the different coloured ellipses in Figure 2 above).

- Group 1

This group included segments 1, 3 and 4. This group is typified by people who are relatively willing to act and have relatively high potential to do more. Segment 1 are already active, but, because of their commitment and strong pro-environmental beliefs, are prepared to do more. People in segment 3 have less conviction in their environmental views and are less active than segment 1 but being environmentally friendly fits with their self-identity and they are willing to do more. People in segment 4 have similar pro-environmental beliefs to segment 1 but they are relative beginners with environmental behaviours and very willing to do more, in at least some areas of their lives. Defra argued that the best way to engage people in this group with sustainability is to tackle external barriers such as information, facilities and infrastructure and to engage people through communications, community action, and targeting of individual opinion leaders. - Group 2

This group included segments 2 and 5. These segments need different approaches to encourage people to be more environmentally friendly and to act in sustainable ways. People included in segment 2 are already active, though driven by a motivation to avoid waste. They have high concerns about changes to the UK countryside and have concerns about other countries not acting. People in segment 5 tend to be more dependent on behaviours becoming the norm before they will act; they are more embarrassed to be green. However, they are willing to do more to achieve sustainability than people in segment 2. Defra argued that the best way to encourage people in this group to act sustainably is to provide fiscal incentives or for businesses and government to lead by example. - Group 3

This group included segments 6 and 7. People here are generally less willing to act and are less likely to be open to voluntary engagement or exemplification by others. Defra argued that the best way to encourage people in this group to act sustainably is to implement interventions of ‘choice editing’ in product availability or, where necessary, regulation.

Research by the UK Behavioural Insights Team

The UK Behavioural Insights Team was established in 2010 to provide an evidence base for government programmes that aimed to influence individual behaviour.

Many of the most pressing public policy issues we face today are influenced by how we, as individuals, behave. For example, we can all cite instances in which we know that we should act differently in our own self-interest or in the wider interest, but for one reason or another do not. The Behavioural Insight Team acknowledges that the traditional tools of Government have proven to be less successful in addressing these behavioural problems (O’Donnell, 2012). To this end, it is necessary to think about ways of supplementing the more traditional tools of government, with policy that helps to encourage behaviour change of this kind. This is what the Behavioural Insights Team seeks to achieve and it supports Government departments in designing policy that better reflects how people really behave, not how they are assumed to behave.

Governments are often reluctant to openly attempt to influence people’s values, and the Behavioural Insight Team draws heavily on work by two behavioural economists (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008), which is seen as offering a ‘value-neutral’ approach to behavioural change. Indeed, the team is often referred to colloquially as the ‘Nudge’ team (after the title of Thaler and Sunstein’s book). Thaler and Sunstein describe their approach as focusing on ‘decision architecture’, but it shares a great deal of common ground with the principles of social marketing the systematic application of marketing concepts and techniques to achieve specific behavioural goals relevant to the social good.

Think about: How useful are these frameworks for developing both sustainability policy and tools to help individuals and networks progress their own sustainability?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free