“Fools” and disability in the Tudor court

“Fool”, sometimes used interchangeably with “jester”, is an evocative term. It conjures up imagery of elaborately dressed entertainers who juggle, sing, and tell jokes. However, the subject is far more complicated and sometimes uncomfortable. Research suggests that many “fools” working in the Tudor court had learning disabilities that were considered advantageous for their work. The word “fool” was common to both Middle English (fōl) and Old French (fol). In the Tudor period it was used both to describe someone who had physical and learning disabilities, and someone who imitated characteristics of disability for the sake of entertainment.

In this article we will use the term “fool” to explore this complex subject. We are aware that the term is offensive and problematic and we hope that our readers will not be upset or offended. However, if you have any concerns about this content, please let us know via the Future Learn website.

Defining the position and situation of “fools” in the Tudor court is not straightforward. While many of these people seem to have been highly valued and well cared for, others were not paid and did not enjoy personal freedom. This article will introduce this complicated subject and explore the lives of two specific “fools”: “Jane the Fole” and William Somer. The fact that Jane worked at the heart of Tudor court from at least 1535 until 1558 and yet we do not know her surname is perhaps indicative of contemporary attitudes to these lives.

“Fools” at the Tudor court

The Tudor court liked to be entertained and at any one time there would have been numerous musicians and other entertainers. On special occasions the number of performers would have swelled, as the best entertainers were brought into court on a temporary basis. While evidence suggests most entertainers were men, there were some female “fools”. For example, Thomasin de Paris (sometimes called Thomasina) entertained Elizabeth I from 1577. Wardrobe accounts recording the making of cloths for Thomasin describe her as “our woman dwarf”, and it may have been that she was of short stature. Renaissance courts valued and indeed competed for the most versatile and unique performers. This was yet another way in which courts projected their power and status.

Court entertainers were important throughout history and are traceable at least back to the courts of ancient Rome and China. Evidence for “fools” at the Tudor court spans the reigns of all Tudor monarchs. In Henry VII’s court we find “fools” called Peche (or Pache) and Dik as early as the 1490s. Numerous “fools” worked at the court of Elizabeth I, including Jack Grene and Richard Tarlton. “Fools” were experts at entertaining the court in which they lived and their work was highly valued.

Incomplete records

Sadly, evidence for the lives of these people is very incomplete and we often try to make assumptions based on incomplete information, such as financial accounts. It is hard to ascertain the great range of skills they employed in their work and every individual had specific talents and a unique repertoire. While some were skilled at comic wordplay and acting, others offered comfort and emotional solace. These attributes often put them in high demand and finding the best “fools” to entertain royal court was given considerable time and attention.

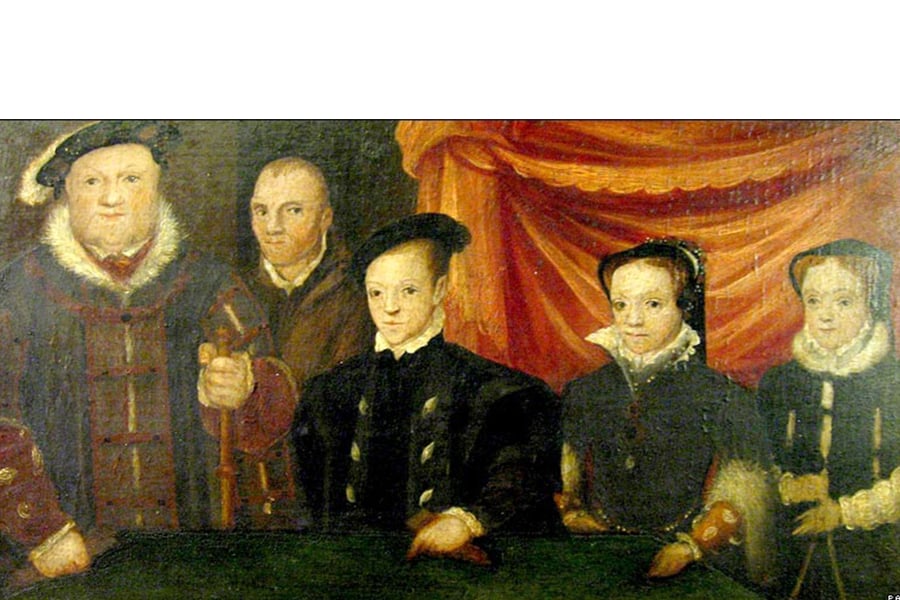

A painting of The Family of Henry VIII, by an unknown artist, c1545. The figures seen through the arches are thought to be “Jane the Fole” and Will Somer and his monkey on the right. Royal Collection Trust © HM King Charles III, RCIN 405796

“Fools” and disability

Many entertainers at the Tudor court had a variety of learning disabilities. The charity Mencap defines a learning disability as:

…a reduced intellectual ability and difficulty with everyday activities – for example household tasks, socialising or managing money – which affects someone for their whole life. People with a learning disability tend to take longer to learn and may need support to develop new skills, understand complicated information and interact with other people.

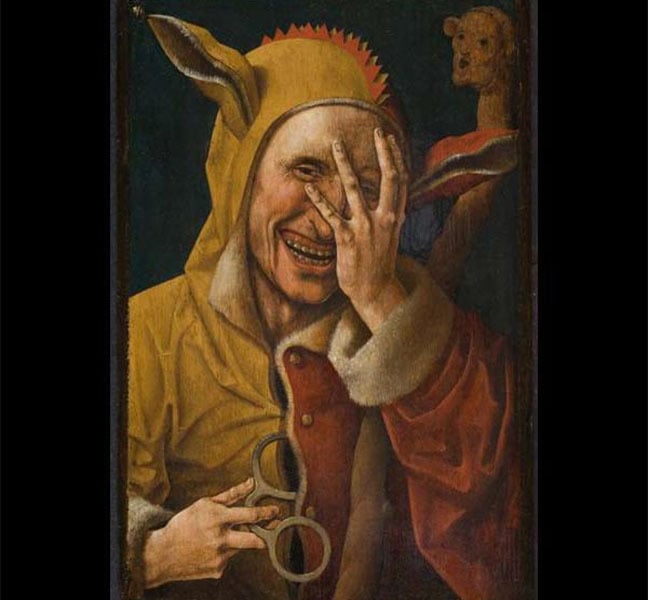

The Laughing Fool, attributed to Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, c1500. © Davis Museum at Wellesley College

“Fools” and freedom

‘He [Henry VIII] the other day nearly murdered his own fool, a simple and innocent man, because he happened to speak well in his presence of the Queen and Princess, and called the concubine “ribaude” [whore] and her daughter “bastard”. He has now been banished from Court, and has gone to the Grand Esquire, who has sheltered and hidden him.’

While “fools” sometimes had privileged positions at court and were granted comic dispensation to speak freely, this freedom evidently had limits.

“Jane the Fole”

Two famous “fools” at the Tudor Court were “Jane the Fole” (d c1558) and Will Somer (d 1559). Both people are known to us from paintings, as well as documentary sources. The inclusion of both of these “fools” in the Family of Henry VIII painting (on display until late October 2023 in the ‘Haunted Gallery at Hampton Court Palace, and returning early in 2024) is a striking indication of their status at court, and the status that they conferred upon the King.

Jane first appears in the accounts of Anne Boleyn for December 1535, when green and red fabric was purchased for the dress of ‘her Grace’s woman fool’. After Anne’s execution, she seems to have been moved to the household of Princess Mary, where she was provided with her own horse. Accounts confirm that Jane participated in courtly entertainments, like riding and sewing. However, the Princess used to shave Jane’s head once a month, which was a practice common with male “fools”. So, while in some ways integrated into the court, Jane was also made to look distinctive.

The Family of Henry VIII (detail) c1545, showing “Jane the Fole”. Royal Collection Trust © HM King Charles III 2023

In October 1544 Mary relinquished Jane to the household of Katherine Parr, where she was gifted with a little flock of poultry which she looked after in a corner of the Privy Garden. The Queen also had a male “fool” called Thomas Browne, who had previously served in the household of Elizabeth Grey, Lady Audeley, who died in earlier that year. Jane disappears for many years from record but in April 1554 she was back in Mary’s – now Queen Mary – household. Mary bought her an expensive wardrobe on this date, perhaps relieved and happy to have her back in her service. When Jane was ill a few years later, Mary paid for her care. After the Queen’s death in 1558, Jane disappears from the records, she may have died the same year but we may never know for sure.

Will Somer

Will Somer (or Sommers) may have been in Henry VIII’s service as early as June 1535 and would go on to serve at court until 1559. Historians have debated whether Somer was an “artificial fool”or “natural fool”. Records in theatrical literature from after Will’s death suggest he was an “artificial fool”. However, court records from 1551 show money paid to a man called William Seyton to ‘keape’ him, and money for men to do his laundry and shave him. This might imply that he needed someone to take care of him or it might be an indication of his later age or status.

The Family of Henry VIII (detail) c1545, the figure on the right carrying a monkey is thought to be Will Somer. Royal Collection Trust © HM King Charles III 2023

Somer was known for his clever wordplay, which was quoted by contemporaries at court. Indeed, courtier and writer Thomas Wilson included in his publication Arte of Rhetorique, Somer’s words to Henry VIII (who was then in want of money): ‘You have so many Frauditors, so many Conveighers, and so many Deceivers that they get all to themselves.’ Frauditors, Conveighers, and Deceivers was a pun referring to financial terminology: auditors, surveyors, and receivers.

Several contemporary images of Somer survive. In the aforementioned, The Family of Henry VIII painting he is shown with a monkey on his shoulder. He was also depicted in a psalter prepared for the use of the Henry himself. The image depicts Henry VIII as David, and refers to a verse from Psalm 52 which states, ‘The fool has said in his heart, There is no God.’ While the depiction of Somer (one of Henry’s actual “fools”) was perhaps a visual pun, it is also a clear indication of his importance at Court.

Somer remained as a favoured “fool” throughout the latter years of Henry VIII’s reign and can be found in the records frequently accompanying the King on the royal progress. He remained in royal service for many years after Henry’s death, and often took part in royal revels. Somer did not disappear from royal records until after the coronation of Elizabeth I in January 1559. He died on 15 June 1559 and was buried in St Leonard’s Church in Shoreditch, London. Many Tudor “fools” and actors were later buried in that church.

Henry VIII playing the harp, and his court jester, William Somer from the Psalter of Henry VIII, 1530-47. ©British Library

A new inter-disciplinary approach?

The complex history of disability in the Tudor court requires considerable new research. We must re-evaluate the fragmentary and often inconsistent evidence for the lives of these people. Recent studies of “fools” in the Middle Ages have identified interesting trends in the historiography of the subject and advocated a more inter-disciplinary approach to the study. Bringing together historians, linguists, sociologists, and other academics to work with current experts in disability studies, including those with lived as well as learned experience, will surely greatly enhance our understanding of this fascinating but complicated subject.

Discussion

It is impossible to understand what any of the entertainers working at the Tudor Court felt about their work and whether they considered themselves exploited. The Tudor Court was a complicated world where status and influence dictated opportunity and freedom, and almost everyone lived in fear of a dramatic, even fatal, fall from grace.

- Do you think “fools” were exploited?

- What were the advantages and disadvantages of being an entertainer in the Tudor court? Consider the potential subversive and satirical role of court jesters in critiquing the monarchy and social norms of Tudor society. How did their unique status grant them a degree of agency and influence within the Tudor court?

- How do you think entertainment and performance practices today reflect the culture of the Tudor court?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free