Zoroastrianism: Settlement of Parsis in Bombay

Share this step

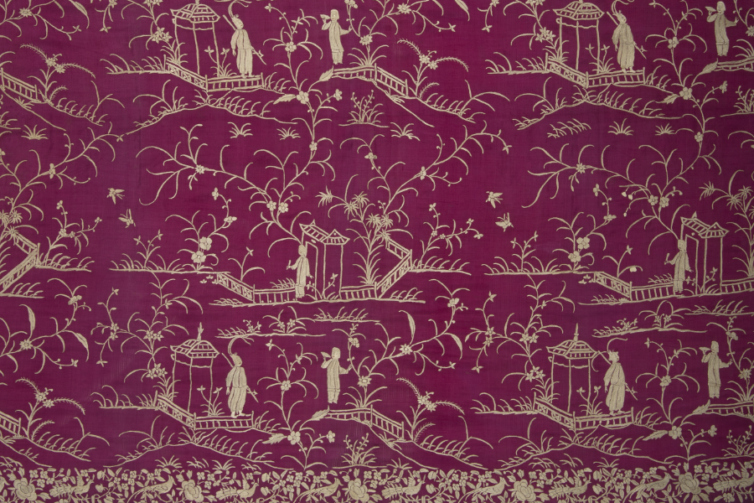

By the early nineteenth century, Parsis had established a lucrative trade with China, the principal exports being cotton and opium. They also dominated the shipbuilding industry, which meant they could trade with countries worldwide, including America and Australia. Their fast-moving clippers would return to Bombay with their holds full of goods such as tea, silk brocade, and beautifully embroidered sari lengths, as well as lacquered furniture, fine porcelain and portraits painted by Chinese artists.

A Wadia Ship, East Indiaman Earl Balcarres, built by Wadia and Company, 1810. Photograph courtesy of Rusheed Wadia in A Zoroastrian Tapestry: Art, Religion and Culture © Pheroza J. Godjrej, 2002

Wooden cupboard with carving of Zarathushtra, from the Alpaiwalla Museum © 2013 SOAS, University of London – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

Parsis and the British

Parsis were ideal trading partners for the British. They were not restricted to rules of caste regarding the work they undertook. There were no restrictions on the employment of women or religious bans on, for example, the growing of crops to make alcohol:

“There was the Paddy Goose, the Green Railing Tavern and the Parsi George, ‘reserved for the jolly Parsi who would like to have bouts, specially of his favourite ‘Gulabee Mowra’, liquor of rose and jungle flower in his own fashion’ ”(from A Zoroastrian Tapestry: art, religion and culture)

British officialdom from the Governor down enjoyed lavish hospitality from Parsi families such as the Wadias, the Jijibhais, the Banajis and the Readymoneys, who made fortunes from the opium trade. This arrangement suited the British when sanctions were imposed on the opium trade as it avoided their involvement with the export of illegal goods. Such interaction undoubtedly had its advantages for the Parsi community: ‘The monied classes generally are favourable to us, they enjoy a degree of security under our Government which they never experienced under native rule’, wrote Lord Elphinstone to Lord Stanley in 1859.

Hirjeebhoy Merwanjee Wadia (1817–83), Jehangeer Nowrojee Wadia (1821–66) and Dorabjee Muncherjee Nanjivohra, by J. R. Jobins, 1842. From the collection of Hameed Haroon © 2013 SOAS, University of London – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

A group of eminent Parsi industrialists of Bombay. Photograph by Raja Deen Jayal in A Zoroastrian Tapestry: Art, Religion and Culture © Pheroza J. Godjrej, 2002

Close contact with the British and European cultures changed the lifestyles of wealthy Parsis. European dress became fashionable, and men began to wear suits and waistcoats, bow ties and dressing gowns. In addition, household furnishings began to adorn the great Parsi mansions with crockery, cutlery, and silverware imported from England.

Ratan Jamsetji N. Tata (1871–1918), by Jehangir Lalkaka, 1938. From the Tata Central Archives © 2013 SOAS, University of London – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

19th-century dining room of Jamsetji Tata, from the Tata Central Archives © 2013 SOAS, University of London – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

Both Parsi men and women took up sports popular amongst the English, such as swimming, cycling and, in particular, cricket. As this class of urban Parsis became Europeanised, so they began to distance themselves from the rest of Indian society, which they regarded as backwards:

“The closer union of the Europeans and Parsis is the finest thing that can happen to our race. It will mean the lifting up of a people who are lying low, though possessing all of the qualities of a European race. The complete Europeanisation of the Parsis is now a mere matter of time.” [1]

A painting of Parsi and Hindu cotton merchants during the middle of the nineteenth century. Photograph courtesy of Parsiana © Pheroza J. Godjrej, 2002

Textiles and portraits

The flourishing trade with China meant that Parsi agents stayed there for months at a time. As a result, materials such as brocade and embroidered silks were manufactured especially for the Parsi sari market. A unique Parsi fabric was the garo, a plain satin sari length, usually in a dark colour, covered with embroidery in contrasting shades. Parsi sari brooches were also distinctive insofar as they adopted European designs in their depiction of tulips and lilies, as well as the Victorian fascination for animals and insects such as butterflies and grasshoppers.

Sakerbai Ardeshir Bolton, Bombay, mid-18th century. F.D. Alpaiwalla Museum, Bombay Parsi Punchayet, bequest of the late Enravaz Dubash. © National Museum, New Delhi, 2016 – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

Brooch-leaf with rubies, from the collection of Aban Marker Kabraji © 2013 SOAS, University of London – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

Parsi merchants acquired the taste for portraiture through socialising with the British and doing business with them in the factories of Canton. As a result, they began to commission portraits of themselves and as gifts to bring back to their families and friends as well as to mark important events such as a death in the family or an navjote (initiation to Zoroastrianism). Today, many of these portraits remain as family heirlooms and adorn the fire temples in Mumbai.

Dastur Noshirwan Dastur Kaikhushru Behram Framroz (1822–97), by M. M., Surat, 1898. From the collection of Hameed Haroon © 2013 SOAS, University of London – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

Dhunbai Jamsetji Tata (1861–71), by P. B. Hatte, 1906. From the collection of Hameed Haroon © 2013 SOAS, University of London – The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination Catalogue

Parsis and philanthropy

The founding of a Parsi Punchayat or five-member governing body (c.1672) established Parsi permanent settlement in Bombay as did the building of a Tower of Silence and a fire temple. Endowments for these two establishments continued through the 18th and 19th centuries. Parsis also founded hospitals and schools as a means of distributing wealth for a charitable cause.

Rustom Faramna Agiary, Dadar Parsi Colony (photograph by Nazneen Engineer)

The religious aspect of Zoroastrian philanthropy is upheld both in doctrine and theologically. We have seen in step 1.9 that everyone is accountable for the fate of their soul, and charitable deeds performed while on earth will bring rewards in the afterlife. So religious charity has a long history among Zoroastrians in Iran and Parsis in India. In an account of his travels to India in the 17th century, John Ovington observes:

‘…Their universal Kindness, either in imploying such as are Needy and able to work, or bestowing a seasonable bounteous Charity to such as are infirm or Miserable; leave no Man destitute of Relief, nor suffer a Beggar in all their Tribe …’ [2]

[1] Kulke 1974: 138 who cites The Parsi, Vol I, No 11, p.533.

[2] Firby, p. 145.

Share this

Zoroastrianism: History, Religion, and Belief

Zoroastrianism: History, Religion, and Belief

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free