The Archaeology of Culloden Battlefield in the Early 2000s

Share this step

Culloden was the last battle to be fought on British soil, but it was also the first battlefield in Scotland to be subject to archaeological investigation.

In 2002 and 2006, geophysical survey, excavation and metal detector survey was deployed across the battlefield, parts of which have, since the 1937, been given into the care of the National Trust for Scotland (NTS). The following provides a brief summary of just a few of the conclusions drawn from this archaeological research.

Recovering the Battlescape

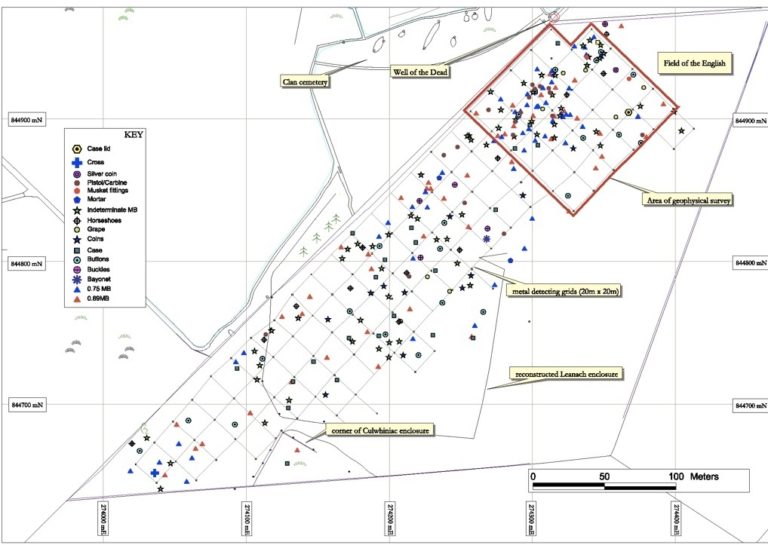

Metal detector surveying located a dense scatter of artefacts from a location measuring around 30 metres by 30 metres.

Metal Detector Findings, Culloden, 2006. ©Professor Tony Pollard

Metal Detector Findings, Culloden, 2006. ©Professor Tony Pollard

Click here for detailed illustration of metal detector results

These objects had been dropped during the vicious hand to hand fighting that came close to turning the tide of the battle in the Jacobite’s favour. There were musket balls, both of 0.69 calibre from the French muskets used by the Jacobites, and the larger 0.75 caliber shot from the Brown Bess musket used in deadly concentration by the British regiments.

Lead shot (left to right) – Grapeshot, Brown Bess musket ball (0.75 calibre), French musket ball (0.69 calibre), impacted musket ball. ©Professor Tony Pollard.

Lead shot (left to right) – Grapeshot, Brown Bess musket ball (0.75 calibre), French musket ball (0.69 calibre), impacted musket ball. ©Professor Tony Pollard.

However, it was not just the musket balls that told the story of what happened here. One of the most evocative discoveries was a bent strip of brass with a crescentic scar etched into one of its edges. This was the back strap from the trigger guard of a Brown Bess, which nestled under the wooden stock where the soldier’s hand gripped the weapon with extended index finger on the trigger. The crescentic scar perfectly matches the size and shape of a 0.69 musket ball. The impact of the shot shattered the wooden stock and snapped this piece off the trigger guard, bending it in the process.

Backstrap from Brown Bess trigger guard (probably from a soldier in Barrell’s regiment) hit by French musket ball. ©Professor Tony Pollard.

Backstrap from Brown Bess trigger guard (probably from a soldier in Barrell’s regiment) hit by French musket ball. ©Professor Tony Pollard.

It is possible if not probable that the ball went on to injure the soldier or even to kill him. The velocity evident from the impact indicates that the shot was fired at close range, probably from just a few metres. This evidence fits well with the orders of the day issued by the Jacobite commander Lord George Murray, in which he stated that guns were not to be thrown away (the tradition being for muskets to be dropped after firing a disruptive shot and then going in with the sword). Murray was keen that the Jacobite army fight along European lines and this order fits well that aspiration.

Also contained within the debris field on the British left were a number of pistol balls. These weapons have a very limited effective range and so are a clear indicator of close quarter combat. These along with other artefacts, including further pieces of broken musket fittings, build up a picture of the crisis which occurred on the British left.

The Road to Defeat

Public disquiet about a road disrespecting the Jacobite graves had a long history at Culloden and ultimately led to the Roads Department relocating it some 200 metres to the north. The original road was simply covered with earth where it crossed the battlefield. Prior to the removal of trees, the road passed through the forest with the graves visible in clearings immediately adjacent to either side of the road.

The reality is however that the road has been wrongly maligned. Rather than being uncaringly built through the clan cemetery, which itself was gentrified through the placement of stone markers and a memorial cairn in the 1880s, the road, or at least an earlier manifestation of it existed at the time of the battle. Not only did it exist but it is now clear that it was actually used by the Jacobites to reach the British left, which stood astride it, at enhanced speed. In short, it was used to deliver the most successful part of the Jacobite charge.

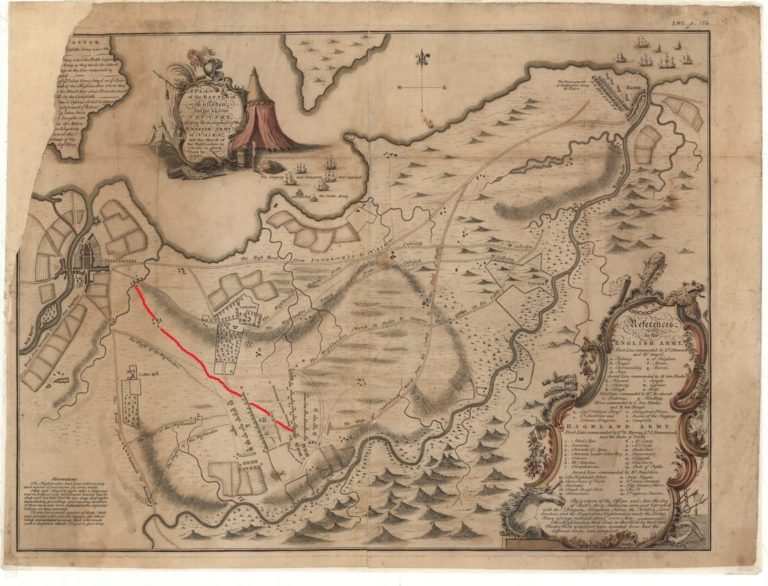

There are two forms of evidence that tell us the road was there in 1746. The first is that it appears on some of the maps drawn up immediately after the battle and which show the disposition of the two armies. Thomas Sandby, a surveyor in the Duke of Cumberland’s staff and a witness to the battle, shows the road passing beneath the centre of the Jacobite line and then cutting across the no man’s land between the two lines before passing under the left of the British army line, where Barrell’s and Munro’s regiments were located.

A plan of the Battle of Culloden and the adjacent country….. Author: Finlayson, John?, 1746. This map places less emphasis than Sandby’s on the road through the battlefield. It is highlighted here in red for ease of identification. ©National Library of Scotland.

A plan of the Battle of Culloden and the adjacent country….. Author: Finlayson, John?, 1746. This map places less emphasis than Sandby’s on the road through the battlefield. It is highlighted here in red for ease of identification. ©National Library of Scotland.

Detailed version of Finlayson’s map

A further clue to the long history of the road was revealed by a detailed topographic survey of the battlefield – which on maps ranging in date from the battle’s immediate aftermath to the modern era, appears as nothing more than flat ground.

The survey revealed a ridge of higher ground running across the field. It was on this natural ridge that the road was constructed – initially appearing as nothing more than a rough track. The ground to the south of the ridge slips away to the degree that there is a marked hollow in a position would be just in front of the British army’s left, and today is still visible to the south of the clan cemetery (and immediately to the north of the area which provided the evidence for hand-to-hand fighting).

If the road assisted elements of the Jacobite force to close the distance between them and the government line, which was throwing cannon and musket shot at them, then the hollow might have provided some of them with an element of cover. This contrasts with the ground to the north of the ridge, and therefore the road, which slopes gently down to the north before levelling off. This ground would provide little cover from fire delivered from the centre and right of the British line, and it is no coincidence that this part of the Jacobite line (the left) got nowhere near the enemy and suffered heavily under fire as they tried to make an advance.

Studying Culloden in interdisciplinary ways aids our knowledge of what happened on the day itself. Historical evidence, such as eyewitness accounts and maps, can be tested against the nature and location of archaeological artefacts. Culloden’s complex battlescape is now better understood as a result.

Further Reading

Tony Pollard, Culloden: The History and Archaeology of the Last Clan Battle (Barnsley, 2015)

Share this

The Scottish Highland Clans: Origins, Decline and Transformation

The Scottish Highland Clans: Origins, Decline and Transformation

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free